In preparation to Janet Jackson’s Vegas residency, each Thursday in the month of May, ETI takes an in-depth look at a significant album from her past. Today, we revisit Janet Jackson’s 2004 album, a lush and preeminently sex-positive album that deserves a reappraisal. On a scale of 1 – 10, we give it a 6.8.

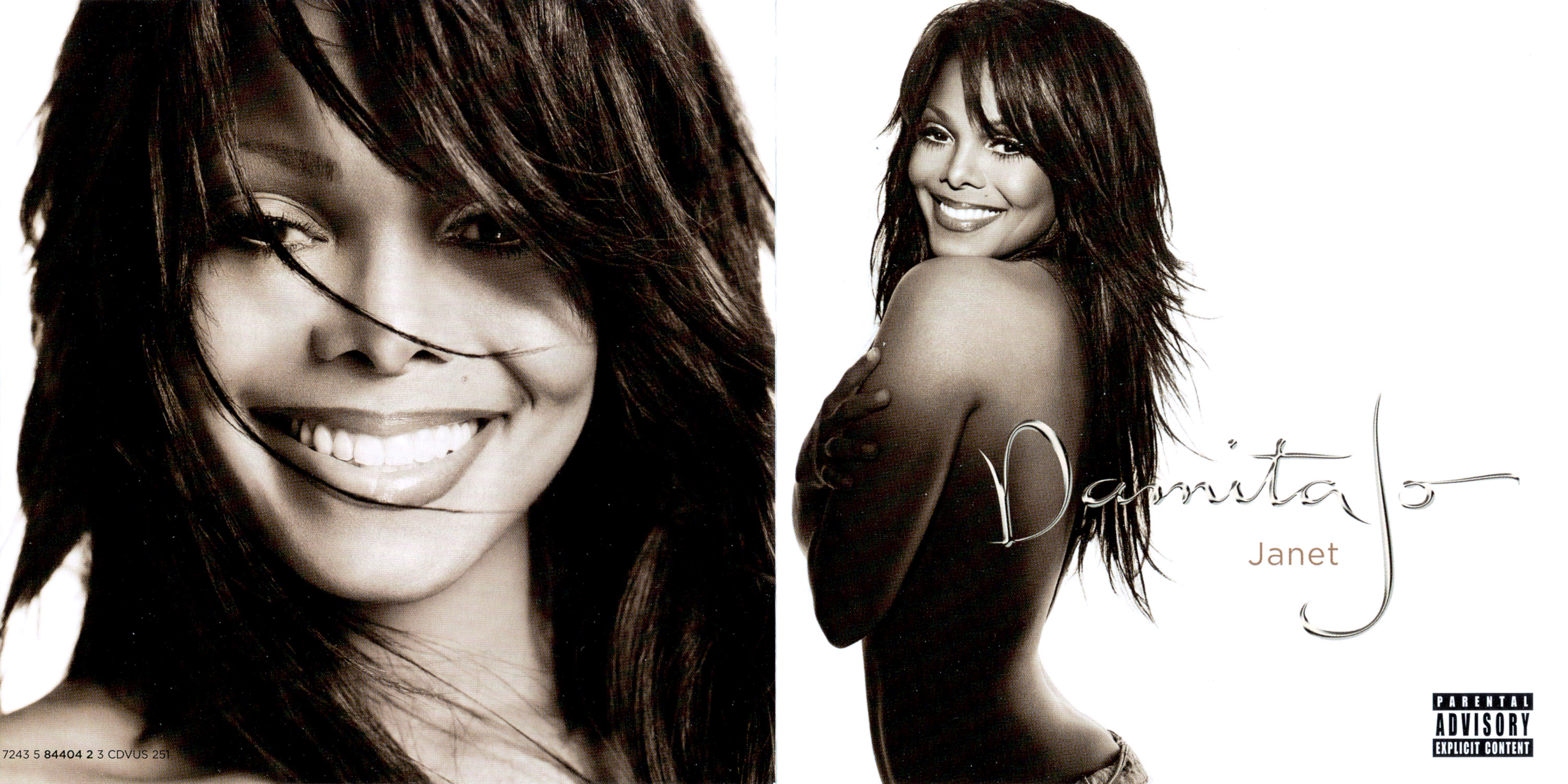

Don’t let that Cheshire cat smile Janet Jackson wears on the cover fool you—this album is something of a tragedy. Damita Jo carries with it inadvertent weight, like a banal conversation with a loved one just a few hours before a fatal accident. What was intended as a long-form expression of nascent love became, in the eyes of many, something repugnant and shameful—a demonstration of Janet Jackson going even further after going too far.

Because it was released in the wake of the 2004 Super Bowl halftime show—that which spawned Nipplegate—Damita Jo was inevitably associated with a debacle that found a single, metallic, sun-clad boob eclipsing a universally adored artist’s entire body of work, a catalog so astonishingly consistent at its commercial peak that Jackson’s greatest hits has a greatest hits. Overnight, Janet went from “the normal one” to yet another wacko Jackson.

But Damita Jo wasn’t a mere casualty of circumstance. It was a response to the uproar. Humid with shameless sexuality, it pointedly doubled down on the sensuality that for a decade had been pervading Jackson’s artistry (including that Super Bowl performance). Jackson could have reined in this extended meditation on the joy of sex—an “MTV News” report that ran mid-January 2004 suggested that she still had weeks of work left on the album after the Super Bowl. Instead, Jackson completed her vision. “There were people who wanted me to take certain songs off the album ’cause they thought it would pose a problem, but that would be changing who I am,” Jackson said on “Good Morning America” on March 31, 2004, the day after Damita Jo’s release. “And I’ll never do that for anyone.”

Jackson might as well have been attempting to fight a fire by singing it a lullaby. Virtually every interview she sat through during the Damita Jo press cycle touched on the Super Bowl, to Jackson’s visible discomfort. Worse yet, it was clear that it was open season on her body: Jay Leno solicited a kiss on air (“That was great…you’re very good at that,” he said after the peck), UK chat-show host Jonathan Ross noted, “What a pretty face you’ve got,” and David Letterman grilled the usually unflappable Jackson enough to exasperate her. “Can we talk about something else ’cause I don’t want to focus on my breast?” she asked after about 10 minutes worth of Super Bowl questions.

In recent years, Jackson’s career has undergone a general critical reassessment thanks in no small part to Black Twitter and the objectively galling decision to have Justin Timberlake perform at the 2018 Super Bowl. Largely ignored by listeners and received tepidly by critics, Damita Jo is something of a stain on Jackson’s recording legacy, the first in a series of commercial disappointments that quantified how the mighty had fallen.

Yet Damita Jo deserves our attention and, yes, justice, not just as a reparative formality but because its specific depiction of sexuality in a mainstream forum—a superstar’s major-label, highly anticipated album—is extraordinary.

Damita Jo was an exploration of the crucial role that sex plays in a new relationship—a basic truth that is generally glossed over in mainstream pop culture’s sanitized portraits of young love. Art that does examine the simple fact that new couples tend to fuck a lot—like Nagisa Ôshima’s 1976 film In the Realm of the Senses, or Gaspar Noé’s Love from 2015—often finds a legacy of notoriety. Damita Jowas inspired by Jackson’s relationship with producer Jermaine Dupri, whom she had been dating for about a year and a half when the album was finally released.

“It’s an album about love,” Jackson told Ryan Seacrest, and that was a line she’d repeat a few times during that press cycle. You could interpret this as spin for daytime television, or take her at her word: Damita Jo’s thematic foundation of love necessitated frank discussions of sex. Focusing on love didn’t whitewash the sex; it contextualized it. You could further, as many critics did, suspect that Jackson was being provocative for the sake of selling records, or you could trust her as an artist who had long earned that trust. “A lot of people know that sex sells, and I think they use that. For me, it’s something that’s true to me—my friends will tell you that sex is truly a big part of my life,” she told Blender.

Jackson’s matter-of-fact presentation of sex made her quite radical in the face of America’s inborn puritanism. The sex that Jackson had written and sung about, particularly on Damita Jo and its 2001 predecessor, All for You (Jackson’s swinging single album, recorded in the wake of her split from her husband of nine years, Rene Elizondo Jr.) was presented as free of consequences. These were fantasies on top of fantasies, a meta-utopia in which a woman and superstar could express herself so explicitly and remain unscathed by the shame. That Jackson chose mostly mid-tempo R&B of the liminal, undistinguished mid-aughts variety to deliver Damita Jo’s subtle treatise surely wouldn’t convince naysayers who rolled their eyes at yet more baby-making music in a genre full of it from an artist who’d been inviting us to her bed regularly for over a decade.

Sex, Jackson reminds us at the offset of Damita Jo, is as crucial to our conception of her existence as entertaining. “I do movies, I do dance, I do music/I love doin’ my man,” she sings in the title track, whose propulsive hook is heralded by an ascending horn figure, recalling some cheery ’70s sitcom theme song. On Damita Jo, sex is alternately found in a club’s dank corners and is so dressed up in euphemism as to sound like something out of old Hollywood. On “I Want You,” a Kanye West co-production, she coos, “Have your way with me,” over a sample of B.T. Express’s “Close To You” that’s pitched up so that its strings take on the frantic emotional timbre of a Douglas Sirk movie.

Damita Jo further explores the theme of Jackson’s criminally slept on 1996 slow jam “Twenty Foreplay,” that of insatiable horniness. (“Yes, I need it/Twenty-four hours a day,” she cooed on that track.) It is an any time/any place ethos as a lifestyle. On the go-go inflected stroll of “Spending Time With You,” Jackson sings of wanting to “Use all our energy/Under the moonlight making love.” On the album’s first single, “Just a Little While,” which combines frenetic breaks, elements of ’80s new wave guitars, and keyboards almost certainly inspired by Prince’s “Dirty Mind,” she frets about burning her lover out and resolves that lest her unyielding sex drive be a distraction, “Maybe I’ll just lay around/Play by myself.”

Pleasure is Jackson’s principle here. Her songs say little of the object of her desire; these odes are to love itself. They center Jackson and bespeak a passion for passion, sex for sex’s sake. This is never more apparent than in the oral suite of “Warmth” and “Moist,” the former of which rhapsodizes giving a blowjob in a parked car and finds Jackson singing with…something in her mouth that’s clearly supposed to be and very well might have been a penis. (When I interviewed her in 2009 during a Discipline junket, she was happy to uphold the song’s mythos, telling me, “There was something in my mouth” during the recording of the track.) “Warmth” is more a sound sculpture than a song, the murmurs and moans as crucial as its faint hook. “Now it’s my turn,” she says at the conclusion of “Warmth,” which flows into “Moist,” a song about receiving oral sex.

Combined, they constitute “active” and “passive” roles in such configurations and underscore the sense of versatility that pervades open-minded sex regardless of gender. Jackson, she’ll have you know, identifies as a bottom—she reportedly told the sea of gay men that watched her headline the Dance on the Pier at the end of New York’s Pride festivities in June 2004. But her lyrics make it clear that Jackson is more specifically a power bottom (the premise of her smash “All for You”—which finds her demanding, “Tell me I’m the only one” moments after admiring a stranger’s package—totally gives her away).

Damita Jo is not just rare for being a piece of mainstream erotica authored by a black woman—it’s also mainstream erotica that isn’t mired in darkness or shame. At its most explicit, Jackson’s dank 1997 masterpiece The Velvet Rope threw us in the dungeon for some bondage play. Damita Jo, in contrast, is largely upbeat if not precisely uptempo. One of her most unwaveringly R&B-oriented collections (again heavily assisted by the production/writing team of Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis), Damita Jo’s tone is bright and breezy. Multiple songs conjure island imagery, and yes, those islands are where people fuck.

That aforementioned smile that graces the cover is reminiscent of the impossibly pneumatic men that Tom of Finland drew in all sorts of carnal configurations, who loved every second of the sex they had with each other. Talk about gleeful, powerful bottoms. In an interview with famed biographer David Ritz in Upscale, Jackson took issue with the suggestion that she had a sexual obsession. “Obsession feels like a judgmental term to me, and when it comes to sex, I try to throw judgments out the window,” she said.

But a lack of shame from within does not inoculate the shame that comes from without. While Damita Jo had its share of enthusiastic reviews (notably, Ann Powers’ four-star write-up in Blender), it seemed to bore and baffle many critics, most of them men. For Rolling Stone, Neil Strauss wrote that Damita Jo “smacks of trying too hard,” while David Segal at The Washington Post said the album “has about it a hint of desperation.” For Entertainment Weekly, David Browne said that Jackson “works so hard at being sexy and provocative that she’s rarely either.” Even Alexis Petridis’ otherwise gushing review for The Guardian (“the results are astonishing”) took issue with the album’s “lyrical monomania,” in which “she puns wearingly on phrases like ‘doing it’ and ‘coming,’ like a demented 14-year-old boy.”

While it’s clear today that Damita Jo didn’t have a sex problem, it did have a specificity one. A terrific track like “R&B Junkie” doesn’t have very much to say—it’s a hazy salute to old school R&B in which Jackson references dances like the wop, the cabbage patch, the electric slide, Vaughan Mason & Crew’s “Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll”…and not much else. (However inept it is at telling, though, certainly basing a song around a sample of Evelyn “Champagne” King’s glistening boogie classic “I’m in Love” is a way of showing the degree to which Jackson was an R&B junkie.)

Accompanying all the dirty discourse was Damita Jo’s stated theme of presenting sides of Jackson she’d never showed off in public—namely the no-fucks-giving Damita Jo (her middle name) and all-fucks-taking Strawberry. But these characters were lightly sketched, at best. Sure, a Janet Jackson album had never been this sexually saturated, but anyone paying attention knew she’d been DTF for over a decade by that point. And no one would think to cross her after she spat, “No my first name ain’t Baby/It’s Janet/Miss Jackson if you’re nasty,” way back in 1986. So how did Damita Jo enhance our understanding of Janet Jackson? Pointedly, it didn’t.

In fact, these “characters,” which the album more or less abandons explicitly five tracks in, elicit more questions than answers. The album contains a leitmotif of Jackson telling what she’s not telling: “There’s another side/That I don’t hide/But might never show,” she sings in the title track. You could feel duped walking away from this album, advertised as a confessional, knowing about as much about Jackson as you went in. But for an entertainer who kept her nine-year marriage a secret until it was ending (going as far as lying to Oprah about it during The Velvet Rope promo), being hawkish about her own narrative is its own sort of expression. The masks and characters she adopts don’t illuminate different sides of her, rather, they protect something she refuses to disown.

All is redeemed by her winsome delivery, though. Jackson doesn’t have a technically great voice, but she is a great singer (as such, Christina Aguilera is her precise inverse). She wraps her throat around her songs with gusto, performing with conviction and, within an evidently limited range, works with a seemingly infinite palette of soft: giggles, moans, whispers, mews, tweets. She has a nimble sense of rhythm that makes vocal pitter-patter around her beats. She doesn’t have pipes that will blow the ceiling off a church, but she’s such a deft performer and because she, Jam, and Lewis knew exactly what to do to enhance her limitations, propping up her main vocal in pillows and pillows of harmonies (see the luscious “Truly”). Nothing about her voice aesthetically suggests power, but what is it if not almighty power to be able to transcend notions of traditional proficiency?

None of Damito Jo’s singles went Top 40 in the U.S, but the lack of hits means that the album plays today as a single statement without the distraction of external cultural attachments to its songs. (It’s also a reminder that pop culture has no obligation to fairness if songs as sublime as “Truly” and “Island Life” should exist in neglect.) That Jackson’s commercial downturn happened to coincide with an album in which she was adamant about her status as a regular person who does regular-person things like fucking feels like some kind of thematic kismet. Damita Jo’s explicitly rendered humanity—in its intent and its performances—ultimately sells the sexual content of the album as part of a real human’s functions and desires, as opposed to a crass marketing angle. Between songs, on her trademark interludes, Jackson babbles about her love of humidity, Anguilla, dusk, and music, aware that life is in the details that outsiders might find extraneous. The glory and the tragedy of mortality spread across Damita Jo like the smile on Jackson’s face. Here I am, she was saying, naked as the day I was born, take it or leave it. Most people left it. That was their loss.

You can check out the latest casting calls and Entertainment News by clicking: Click Here

Click the logo below to go to the Home Page of the Website

Click the logo below to follow ETInside on Twitter

Click the logo below to follow ETInside on Facebook

Click the logo below to follow ETInside on Instagram

Click the logo below to follow ETInside on Pinterest

Click the logo below to follow ETInside on Medium